The Tragedy of Identity

George Herbert Mead is a central figure in sociology and social psychology. For those who don't know him, he is the one who proposed the theory of the "Generalized Other". A sort of hyperbole of common sense. For an exhaustive understanding of what I'm trying to say, it's worth dwelling a few lines on this concept of "Generalized Other". Let's play.

For Mead, identity or the "self" is not something innate or fixed, but rather a product of social interactions. Our identity develops as we interact with others. In other words, we become aware of ourselves through our relationships with others.

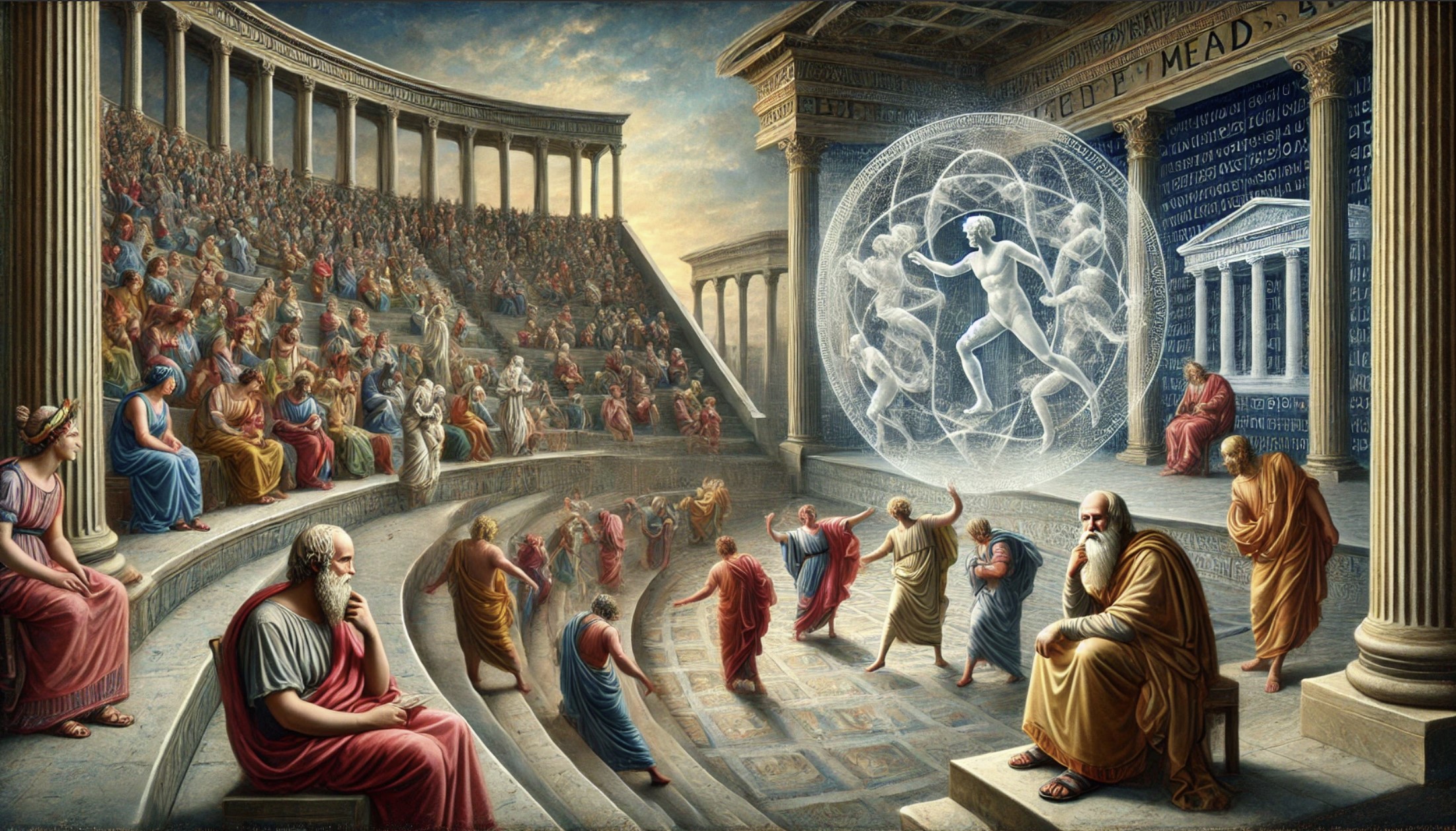

Mead identifies two fundamental phases in the development of the self: play and symbolic play. In play, children imitate the actions of others, allowing them to take on different roles and see the world from different perspectives. In symbolic play, children begin to participate in organized games where each participant has a specific role (for example, playing "home" or "school"). This helps them understand how their behaviors affect others and vice versa.

While play and symbolic play are based on assuming specific roles, the generalized other represents a later phase in the development of the self. The "generalized other" refers to an individual's ability to have a notion of the expectations and norms of society as a whole. In other words, it is an awareness of the attitudes and expectations of the community in general. When an individual considers how they would be judged by general social norms, they are considering the generalized other.

Mead further divides the self into two components: the "I" and the "Me". The "Me" represents the expectations and norms of society – essentially, it is what we have learned from the generalized other. The "I", on the other hand, represents the individual and spontaneous response of the individual to these social norms. At any given moment, the individual is negotiating between the "I" and the "Me", between their own personal responses and the expectations of society.

Symbolic communication, particularly language, plays a crucial role in the development of the self. Through language, individuals can share meanings, express expectations, and negotiate identities.

In summary, Mead proposes that our sense of self develops through social interactions. As we interact with others and with society as a whole, we form an image of how we are seen and model our behavior accordingly. The generalized other represents the sum of social expectations and norms that influence this process of self-formation.

Symbolic communication plays a fundamental role in tragedy according to Aristotle, especially when analyzing his work "Poetics". Tragedy, for Aristotle, is an art form that imitates meaningful actions through a series of symbols, mainly language, but also through gestures, costumes, set designs and music.

Language, of course, is one of the most powerful tools in tragedy. Dialogues, monologues and lyrics are rich in symbolism. Through words, tragic authors explore deep themes such as morality, fate, gods, honor and shame. Every chosen word, every constructed sentence, serves to convey multiple and profound meanings.

One of the main goals of tragedy, according to Aristotle, is catharsis, a purification or purging of the emotions of fear and compassion. This emotional effect is achieved through a series of symbols and images that resonate with the human experience, leading the audience to an intense emotional response.

Now let's run back in time and sit next to Aristotle on the marble steps of a Greek theater. The game of the self begins, the tragedy takes place.

In Greek tragedy, the actors wore masks. These masks not only represented the different characters, but were also symbols of the roles and identities that those characters embodied. A king wore a king's mask, a woman a woman's mask, and so on. These masks helped visually convey the essence and nature of the character to the audience.

In addition to language, the actions performed by the characters on stage were charged with symbolic meaning. A sacrifice, a kiss, a fight – each action had deep meanings that went beyond mere physical representation.

The very structure of tragedy, with its rhythm of exposition, climax and resolution, served to communicate the relentless movement of fate and the tensions of human life. The cadence of the scenes, the alternation between intense dialogues and lyrical choruses, all contributed to creating a symbolic experience for the audience.

Tragedy, according to Aristotle, was not only a representation of events but an intricate web of symbols that, when correctly interpreted, revealed profound truths about the human condition.

At the beginning of our existence, we find ourselves confronted with a fundamental question: "Who am I?". This question, simple in its formulation but deeply complex in its essence, has guided much of the philosophical and psychological discourse over the centuries.

Aristotle, with his profound reflection on tragedy, has offered us a glimpse into human nature, illuminating the tension between personal desires and seemingly ineluctable external forces. Take, for example, the story of Oedipus. His tragic struggle was not so much with external circumstances, but with his own nature and the decisions made in an attempt to escape a predicted fate. In him, we see the eternal battle of the individual against forces that seem beyond his control. However, Oedipus' tragedy does not lie only in his actions, but in the painful realization and acceptance of his fate. This acceptance, and the catharsis that follows, represents a profound introspection and understanding of the 'self'.

While Aristotle has shown us how the individual can be shaped by external forces, Mead has taken us into different territory, exploring how identity is shaped by our interaction with society. Every time we tell a story about ourselves, we are actually negotiating between our inner vision and external expectations. Let's imagine, for example, a young artist raised in a family of doctors. While his passion pushes him towards painting and sculpture, external expectations may require him to follow in the family's footsteps. Each painting he paints, each sculpture he creates, becomes a declaration of his 'self', an act of resistance against external perceptions.

Mead's theory of mind takes us even deeper into this inner and outer dialogue. When we think about how others see us, we are actually projecting our beliefs, fears and expectations onto them. This projection becomes a fundamental part of our identity. For example, a teacher may see himself as a mentor and guide, but if he perceives that his students see him as boring or severe, this perception could profoundly influence the way he sees and behaves.

This continuous play of tensions – between external forces and internal desires, between one's own perceptions and those of others – creates a mosaic of identity that is constantly evolving. As we move through life, gathering experiences and interacting with the world around us, our understanding of the 'self' deepens and is enriched.

But in reality the question we must answer is whether we are actors or spectators of the tragedy of our life. Maybe it's not us watching the show.